3 decades of warnings of an inevitable Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor went unheeded

HONOLULU - At 12:30 in the afternoon on Dec. 8, 1941, less than 30 hours after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed Congress and the American public in a nationwide radio broadcast, calling the attack “unprovoked and dastardly,” sparking a surge of American patriotism and a sudden new willingness to enter World War II that changed the country’s course drastically.

Roosevelt went on to say in his radio address, “[The] United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific” when it was “suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces.”

But many historians and officials employed by the U.S. government at the time point to decades of failed diplomacy on the part of the U.S. as a clear precursor to the act of warfare carried out on Dec. 7, 1941.

Some officials were warned in clear detail by those with insider knowledge that Pearl Harbor was to be attacked by the Japanese — and some argue the attack could have been avoided altogether had these American officials heeded the warnings.

Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt to Congress on Dec. 8, 1941. (Library of Congress)

WHAT WERE THE WARNING SIGNS?

One of the first warnings came in 1902, while Franklin Delano Roosevelt was studying at Harvard University. A Japanese student told him about Japan’s 100-year plan to take over Asia and the Pacific.

After a visit to Japan in 1910, Billy Mitchell, a Milwaukee native who was then serving in the Army and stationed in the Philippines during WWI, wrote, “That increasing friction between Japan and the U.S. will take place in the future there can be little doubt, and that this will lead to war sooner or later seems quite certain.”

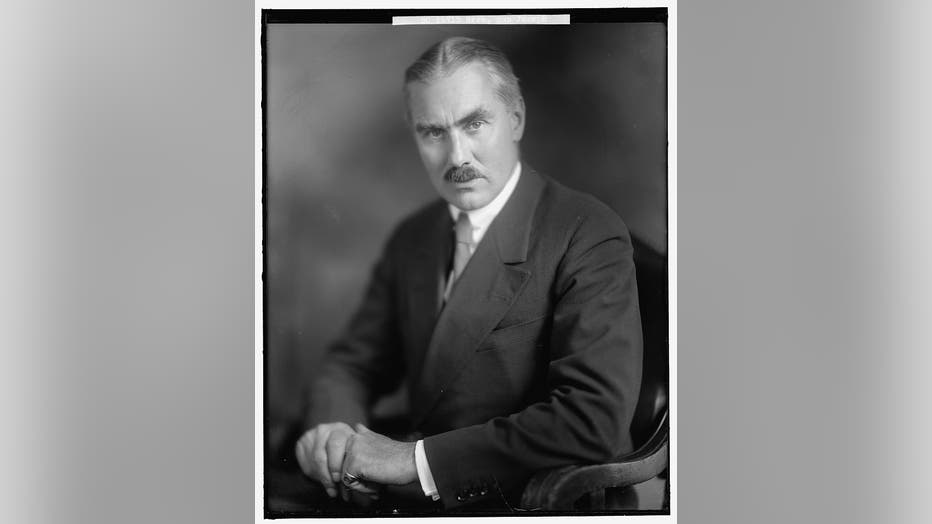

Col. William "Billy" Mitchell (Library of Congress Prints Photographs Division)

After returning stateside as a decorated war hero, Mitchell tried desperately to convince U.S. commanders that one day planes would be able to sink ships — a notion they shrugged off. He also predicted the creation of unmanned aerial vehicles (a.k.a. drones), as well as the evolution of planes to be used in firefighting, evacuating sick and wounded people and spying on enemies.

In 1924, Mitchell toured Hawaii and Asia to inspect American military assets, and the next year wrote a book about his takeaways from analyzing military capabilities of the Asia-Pacific Rim. In his book “Winged Defense,” Mitchell detailed how Japan could carry out an attack on Hawaii, predicting 100 bombers would strike Pearl Harbor’s naval base.

The U.S.S. California is hit during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. (U.S. Navy via Library of Congress)

His eerily accurate prediction was issued 15 years before Japanese bombers fulfilled the prophecy.

Another similar prediction was published in 1925. The British book, “The Great Pacific War,” described a fictitious war in which carrier-based Japanese planes bombed American cities.

For years leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor, Prince Fumimaro Kanoe of Japan had harbored disdain and distrust of the U.S., and he wrote an embittered essay in 1918 warning against British and American racial and economic imperialism.

Prince Kanoe eventually led Japan’s successful invasion of China in 1937, which marked the beginning of the final unraveling of the already-struggling relations between his country and the U.S. and its allies.

By 1941, the warnings couldn’t have been any clearer.

Eric Sevareid, a CBS News journalist and esteemed war correspondent during WWII, recalled, “A young Korean-American would often drop into my Washington office. He was in touch with the anti-Japanese Korean underground. ‘Pearl Harbor’ he kept telling me, ‘before Christmas,’ but he could get no audience at the State Department.”

In Jan. 1941, Ambassador Joseph Grew learned of Japan’s plans to bomb Pearl Harbor from the Peruvian Embassy. The U.S. State Department, headed by Secretary of State Cordell Howe, chose to disregard the warning and continue approaching negotiations with the Japanese from a hard-line stance.

Joseph C. Grew served as the U.S. Ambassador to Japan at the time of the Pearl Harbor attacks.

The U.S. had been able to decode all diplomatic messages from Japan beginning in Sept. 1940, and a year later, Howe knew that the two Japanese diplomats sent to negotiate with the U.S. had been told to keep talking, but that “after Nov. 29, things are automatically going to happen.”

“We had many signs in the wind that something was going to happen,” said Dr. William B. Bader, who worked for the CIA and State Department as a naval intelligence officer in the 1960s before going on to hold a vast array of other government positions.“We believed that the Japanese were going to do something, but we didn’t know what or when.”

Wreckage of U.S.S. Arizona after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. (U.S. Navy via Library of Congress)

A LONG HISTORY OF BULLYING

The U.S. bullying of Japan began with Commodore Matthew Perry’s 1853 invasion of the country, intended to penetrate Japan’s wall of isolation and to open up trade with the U.S. His efforts were successful largely because his men possessed guns, and the Japanese viewed their intruders as barbarians.

Japan emerged as major world power during the Russo-Japanese War, spanning 1904-1905, after destroying the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated a peace treaty, denying the Japanese victory and manipulating the terms to protect American interests in the far east.

Roosevelt sent a stark message to Japan in 1908 via the Great White Fleet, which consisted of 16 battleships. He sent the fleet around the world as a demonstration of American military power, and the fleet’s arrival in Japan signified that the U.S. didn’t intend to sit back and let other countries dominate the Pacific.

Another slap in the face was delivered during the Paris Peace Conference in Versailles in 1919. Japanese leaders requested that the League of Nations adopt a guarantee of racial equality — an idea presented by Prince Konoe. President Woodrow Wilson and the Allies refused.

At the 1921 Washington Naval Conference, U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes convinced the Japanese to take a lesser naval role, imposing a limit of three naval ships to every five British and American ships. This became known as the 5-5-3 rule, which angered young Japanese naval officers — the officers who would rise through the ranks over the next 20 years leading up to the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

When the U.S. passed the Exclusion Act in 1924, it seemed like a whiplash refusal of the Japanese requests to the League of Nations five years earlier. All Japanese immigration to the U.S. was cut off, and all Japanese citizens were forbidden by law to own land in the U.S. — an official policy of racial discrimination.

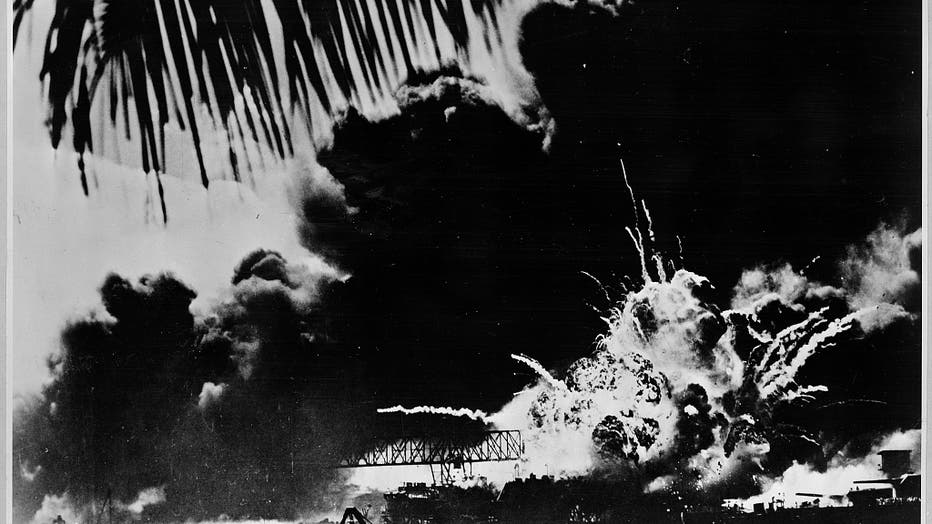

Pearl Harbor naval base and U.S.S. Shaw ablaze after the Japanese attack. (U.S. Navy Photograph via Library of Congress)

HOW DID THE U.S. GET SURPRISED BY AN ATTACK THAT HAD BEEN PREDICTED FOR NEARLY THREE DECADES?

Americans, even those officials serving in government positions, were largely unconcerned with Hawaii as a target of potential Japanese attacks in 1941, betting that any potential attack would be carried out elsewhere.

“In 1941, Hawaii was the center of American peacetime Naval opportunities and was considered one of the best assignments for sailor and officer alike,” Sevareid said.

Other alarms had been issued earlier and had proven to be false, so when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued war warnings to the Pacific on Nov. 27, they were largely ignored in Hawaii.

“If an attack by Japan came, it would probably be in Singapore or the Dutch East Indies, perhaps even the Philippines,” Sevaried recalled of the prevailing mentality of the time. “Not Pearl Harbor.”

Pearl Harbor naval base and U.S.S. Shaw ablaze. (U.S. Navy via Library of Congress)

Tensions between the two rival countries had been exacerbated drastically after a treaty between the French Vichey government gave Japan control of Indochina, and Roosevelt attempted to quell Japan’s expansionist war efforts by freezing all of Japan’s money in the U.S. and imposing an embargo on oil.

By Aug. 1, all trade between the U.S. and Japan had ceased, and the embargo reduced Japan’s oil imports by 90 percent, effectively crippling its ability to push on in the war and likely forcing Japan to retreat until all valuable gains in Asia were lost.

“Not only would Japan be forced to get out of China and all its gains, but the military would completely lose face at home and probably lose power,” said Harvard University Professor Edwin O. Reischauer.

In a final attempt at diplomacy, Japan sent a special envoy, Saburō Kurusu, to Washington.

Discussions were held between Kurusu, Japanese Ambassador to the U.S. Kichisaburō Nomura and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Kurusu and Nomura knew that by Nov. 17, the Japanese fleet was already assembling in the Korean Islands. If no diplomatic settlement was reached by Nov. 29, the fleet would depart for Pearl Harbor.

Wreckage of U.S.S. Arizona following attack on Pearl Harbor. (U.S. Navy via Library of Congress)

Hull believed that the meetings were fruitless and that war was inevitable because of the State Department’s ability to decode Japanese messages, but he had no idea that the Japanese fleet was already in motion.

Some historians and scholars point to Hull’s significant lack of experience in international diplomacy as a major factor in the breakdown of relations which led to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“In a sense, Cordell Hull was an unfortunate person to have in that position at that time. I don’t think he was sensitive to different points of view, systems outside our own system,” said George Kennan, a highly-esteemed historian, diplomat and professor. “He was very rigid on his concept of the law and his concept of what he thought international law was, and the Japanese had very different views.”

“Cordell Hull was a delightful honorable gentleman, naive as a child about international affairs, whose qualifications for presiding over the foreign policies of the United States were almost null,” Kennan added. “He knew nothing about the outside world, and he was not in a position really even if you tried to tell him.”

Kurusu and Nomura called an emergency meeting with Roosevelt on Nov. 26 as a last-ditch effort to reach a settlement — the Japanese fleet had departed and was en route to Pearl Harbor.

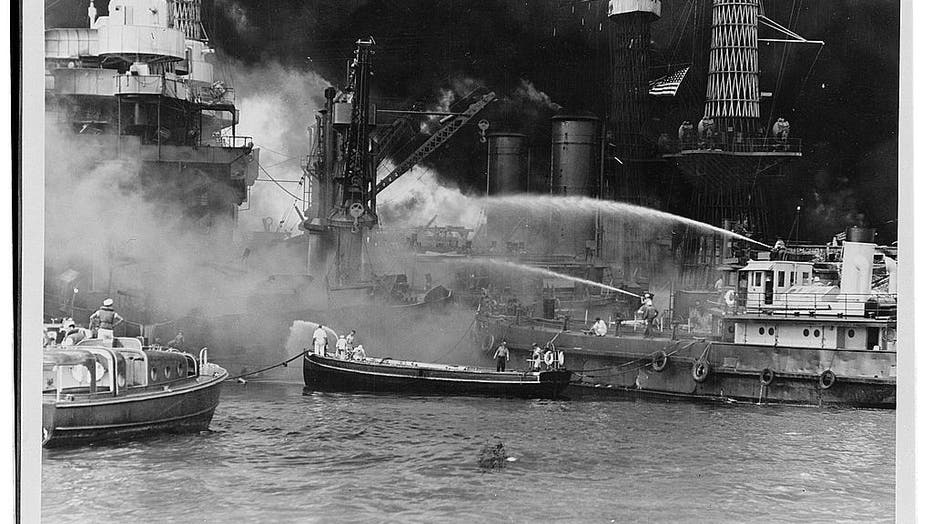

USS West Virginia aflame. Disregarding the dangerous possibilities of explosions, United States sailors man their boats at the side of the burning battleship, USS West Virginia, to better fight the flames started by Japanese torpedoes and bombs. (Office of War Information via Library of Congress)

If negotiations were successful, the fleet would return. If not, the attack on Pearl Harbor would proceed.

Roosevelt rejected Japan’s final offer of diplomacy on Nov. 27 and demanded that it withdraw from Indochina and China. Expecting Japan to refuse, he issued war warnings to the Pacific.

At 7:55 a.m. local time, a swarm of 360 Japanese warplanes descended on the naval base at Pearl Harbor, ultimately destroying five of eight U.S. battleships, three destroyers and more than 200 aircraft.

A total of 2,400 Americans lost their lives in the attack, and another 1,200 were wounded.

Three civilians were killed in this shrapnel-riddled car by a bomb dropped from a Japanese plane eight miles from Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, December 7, 1941

“To one nation, Pearl Harbor was a stab in the back, a day of infamy,” Sevareid reflected. “To another, it was a necessity, a desperate act by a people with their backs to the wall... and historians may argue forever.”

This story was reported from Los Angeles.